All natural aromatic substances that exist in Nature have a purpose other than to smell good in perfumes. In the case of ambergris, it is produced in the stomach of the sperm whale, where it serves to protect the intestinal lining against the tough, horned snout of cuttlefish, a kind of squid that the whale swallows whole. All very practical, as we most assuredly find in Nature. While most teach that it is secreted as vomit, some argue that it also passes through the feces. Some, especially commercial, American perfumers usually avoid it because of legal ambiguities. It was banned from use in many countries in the 1970s, including the United States, because its precursor originates from the sperm whale, which is an endangered species.

All natural aromatic substances that exist in Nature have a purpose other than to smell good in perfumes. In the case of ambergris, it is produced in the stomach of the sperm whale, where it serves to protect the intestinal lining against the tough, horned snout of cuttlefish, a kind of squid that the whale swallows whole. All very practical, as we most assuredly find in Nature. While most teach that it is secreted as vomit, some argue that it also passes through the feces. Some, especially commercial, American perfumers usually avoid it because of legal ambiguities. It was banned from use in many countries in the 1970s, including the United States, because its precursor originates from the sperm whale, which is an endangered species.

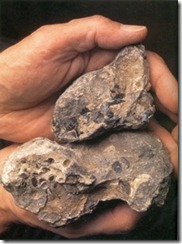

Historically, it was considered the second most treasured commodity to come from the sea, second to pearls. After being excreted by the whale, it would be collected from the surface of the ocean near the islands of Sumatra, Molucca and Madagascar, and was referred to as “the gold of the ocean”. The hardened shape, resembling fossilized lumps of amber (albeit grey in color), thus derived the name “grey amber” or ambergris. It is a known fact that certain kinds of ambergris are known to float in the ocean for up to a hundred years. Ancient Egyptians burned ambergris as incense, while in modern Egypt ambergris is used for scenting cigarettes.

kinds of ambergris are known to float in the ocean for up to a hundred years. Ancient Egyptians burned ambergris as incense, while in modern Egypt ambergris is used for scenting cigarettes.

We humans have chosen to not fully embrace our own animalistic odor and instead we mask it with myriad smelly cover-ups. Probably originating in hygiene and sexual modesty that ultimately fevered the Puritanical movement. The enigma that we are drawn to smells that reflect our deeper centers of pleasure and love perfumes rich in products of animal origin (any animal other than human, that is) only confirms what complex and contradictory beings we are, especially when it comes to sexuality. It is true that those perfumes with a ‘hidden’ pungency, unidentified intellectually in our awareness, are extremely popular.

Avery Gilbert challenges us to stop randomly studying aromatic molecules in the laboratory and to “start observing odor fluency where it happens naturally.” He reminds us that Charles Darwin was a “careful observer” and “attuned to smell”. In Darwin’s words (speaking of the musk deer, another animalic odor): “On the banks of the Plata, I have perceived the whole air tainted with the odor of the male Cervus campestris, at the distance of half a mile to leeward of a herd.” Darwin recorded odors, along with other facts like species, place and time. I mention this because I, like many of you, struggle with adequate descriptors for odors and Avery makes a perfect case for getting out in Nature herself as it might serve both perfumer and writer. Since I, also, cannot disconnect my work with aromatics from the importance and joy of relating to unabashed Nature, I very much like the way he thinks in this regard.

One of the earliest devices for enjoying aromatics in the fourteenth century actually derives its name from ambergris. The ornately designed apple-shaped globe, sometimes decorated with gold and silver, with small individual sections held together with hinges was called a pomander, from the French pomme d’ ambre or apple of ambergris. Originally, a simple, but pungent rolled ball of ambergris would suffice, but art emerged

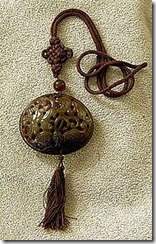

One of the earliest devices for enjoying aromatics in the fourteenth century actually derives its name from ambergris. The ornately designed apple-shaped globe, sometimes decorated with gold and silver, with small individual sections held together with hinges was called a pomander, from the French pomme d’ ambre or apple of ambergris. Originally, a simple, but pungent rolled ball of ambergris would suffice, but art emerged to house the scent, like this lovely ornamented creation pictured here. The chambers were filled with scented paste and powder, using beeswax and other aromatics, each chamber sometimes housing a different odor. Aristocrats of both sexes would carry these devices to occasionally sniff to ward off the malodorous smells of the street. Larger ones were attached by a chain to the belt or worn around the neck and smaller ones, no larger than a thimble, were connected by a tiny chain to a finger ring.

to house the scent, like this lovely ornamented creation pictured here. The chambers were filled with scented paste and powder, using beeswax and other aromatics, each chamber sometimes housing a different odor. Aristocrats of both sexes would carry these devices to occasionally sniff to ward off the malodorous smells of the street. Larger ones were attached by a chain to the belt or worn around the neck and smaller ones, no larger than a thimble, were connected by a tiny chain to a finger ring.

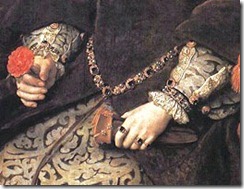

During the Renaissance, the “girdle” (not to be confused with the modern-day “corset”) was an important accessory made of leather, textile or flat metal chain that formed a belt-like strap worn diagonally along the waistline, draping from just above the hip on the right, downward to the left thigh. The girdle was typically accessorized with items like a purse, keys, knives, lockets, girdle books, decorative bangles, or a pomander. The bangles or pendants (just as the pomanders themselves) could be bejeweled, enameled, or decorated with cameos, and were fastened to the girdle with equally decorative clasps. Of course, it was also one of those perfumed fallacies that the pomander would keep one from getting the plague.

was an important accessory made of leather, textile or flat metal chain that formed a belt-like strap worn diagonally along the waistline, draping from just above the hip on the right, downward to the left thigh. The girdle was typically accessorized with items like a purse, keys, knives, lockets, girdle books, decorative bangles, or a pomander. The bangles or pendants (just as the pomanders themselves) could be bejeweled, enameled, or decorated with cameos, and were fastened to the girdle with equally decorative clasps. Of course, it was also one of those perfumed fallacies that the pomander would keep one from getting the plague.

The early gastronomer Brillat-Savarin created a recipe for ambergris-laced chocolate in 1826, perhaps for the tables of Casanova, Madame DuBarry and Madame de Pompadour. And, Nostradamus believed the chewing of lumps of ambergris could increase the production of seminal fluid. Jean Paul Guerlain observed that ambergris “was to perfume creation what cream is to haute cuisine: an exquisite binding agent.” Since we find in history the use of ambergris as a spice in food, his observation is more than metaphorical. Musk and ambergris notes in perfume composition are of great significance and are a used in the composition to produce a sense of pleasure via ancient neural pathways without so much as a conscious thought as to the true nature of the stimulus.

Since we are in the middle of celebrating the Chinese New Year, it is worth mentioning that the Chinese considered ambergris to be a potent aphrodisiac. The ancient Chinese called the substance “dragon’s spittle fragrance”, lending yet another allusion to the current Chinese Year of the Dragon. The early Chinese also used their version of pomanders like this small one pictured.

Since we are in the middle of celebrating the Chinese New Year, it is worth mentioning that the Chinese considered ambergris to be a potent aphrodisiac. The ancient Chinese called the substance “dragon’s spittle fragrance”, lending yet another allusion to the current Chinese Year of the Dragon. The early Chinese also used their version of pomanders like this small one pictured.

In the eighteenth century, it was made into one of those “single-note” perfumes, like jasmine and neroli.

Styles and attitudes change and during the Restoration and into the later years encompassing the July Monarchy animalic scents fell into disfavor. The more erotic scents began to be replaced with less controversial floral and herbaceous compositions. Women became more worried about “being provocative”. The newspaper Les Messager des odes et de l’industrie from 1853 identifies ambergris as “the primary perfume ingredient for women of easy virtue (cocettes) . . . and in the decade just preceding the Revolution, Mercier, the chronicler of social customs wrote that the decline of favorability for scented gloves was due to their “violent odor.” Ultimately, strong animalic scents were banned and only worn by women of questionable morals.

Septimus Piesse, the early nineteenth century chemist-perfumer, lamented that the scent of ambergris “clings pertinaciously to woven fabrics and is still found in the material after passing through the lavoratory ordeal” by which he no doubt means washing of clothes. I would argue that Piesse exaggerated somewhat and that one must always consider the final odor note in a composition after the melding of all others, as well as all other variables when evaluating the odor of an aromatic ingredient of natural origin.

In perfumery, it is the finest of all fixatives and will delay the volatility of other scented ingredients in a composition. It is one of those perfume substances that sometimes draws revulsion when one learns of its origin, however, in the raw it actually has a relatively mild odor – marine, slightly fecal, reminiscent of balsamic leather with a slight wet, sour aspect. And, of course, we must keep in mind that odor can differ greatly from one batch to the next depending on the origin, age and processing method to obtain a perfume ingredient.

At Samara Botane, when we have the material available, we make a strong alcohol tincture using a Soxhlet extraction procedure which can then be diluted to the perfumer’s preference. This process produces ambrox and ambrinol, which are the main odor components of ambergris. In perfumes, once married to other notes, ambergris becomes quite warm, earthy and velvety. Some natural perfumers who wish to steer clear of animal ingredients, appear to get an ambergris doppelganger by combining labdanum, olibanum and vanilla.